I’ve never been hugged by my dad. Growing up, I was under no illusion that I was anywhere near the favourite of his 9 kids.

I’ve never been hugged by my dad. Growing up, I was under no illusion that I was anywhere near the favourite of his 9 kids.

I thought he was harsh, dictatorial, mean-spirited; I couldn’t stand watching him pander to those with social standing. I was appalled when he once grabbed a little Indian kid out of the Odeon by the ear and told him never to come back. The kid had been hawking curry puffs from a basket and the way my dad saw it, was threatening our own livelihood.

He was never quite sure how old I was, let alone remember my birthdays. He once threatened to break my legs for wearing shorts. It was a rough relationship and I used it to milk for sympathy from anyone who would listen.

Ironically it took a privileged Scandinavian to help me see things from a different perspective. I had relayed these stories to Steffen (my boyfriend at the time) in anticipation that it would win me some brownie points; his response took me aback and somewhat annoyed me.

Yes, but did he remember ANY of his kids’ birthdays? Did he hug ANY of his kids? Never having met my dad, Steffen, at all of 21, was nevertheless wise enough to the fact that my dad probably had a tough upbringing and A LOT of responsibilities AND was of a different era and culture where affection was not freely displayed etc. etc. etc. But, but, but – what about his tolerance towards some of my other siblings’ perceived misbehaviour and hardline towards mine? By that stage, even I knew I was splitting hairs.

My dad, Wa Koy Tang, was born in 1927 in Malaysia from immigrant Chinese parents. His dad died when he was some 13 years of age. Dad had to leave school to take up the breadwinner mantle for the family, having only completed primary school education.

There are gaps in my knowledge of his early years; I know he was sent to labour camp during the Japanese occupation of Malaya, where he worked for a not-completely-evil Japanese industrialist.

He was fed a diet solely comprised of yam which made his face swell up – it gave his mom some relief when she finally got to see him after a long absence, thinking he must have been well-fed by his oppressors, when in fact he was severely malnourished and at the brink of death. It was also during this stint in the labour camp that he developed an injury to his knee that was to haunt him late in life.

His marriage to my mom was pre-arranged; he met her when she first got off the boat from China – they were both kids back then. He laughed when he relayed in his twilight years that he thought at the time she was really ugly, with buck teeth.

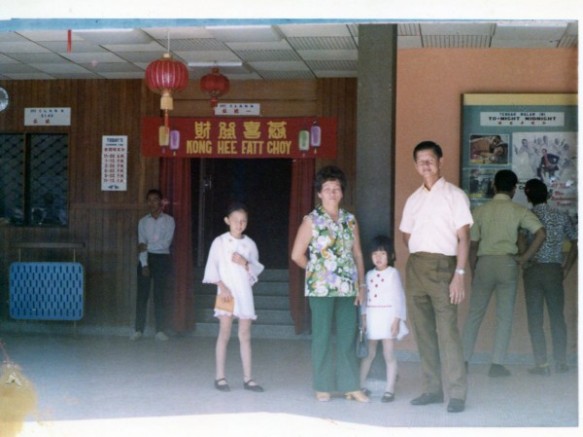

My parents went on to have 10 kids, 9 of whom made it to adulthood. My dad worked 20-hour days 7 days a week – that’s 20 hours of hard, physical labour. He started out selling street food; he was enterprising enough to diversify, eventually taking up a canteen at the Odeon Cinema.

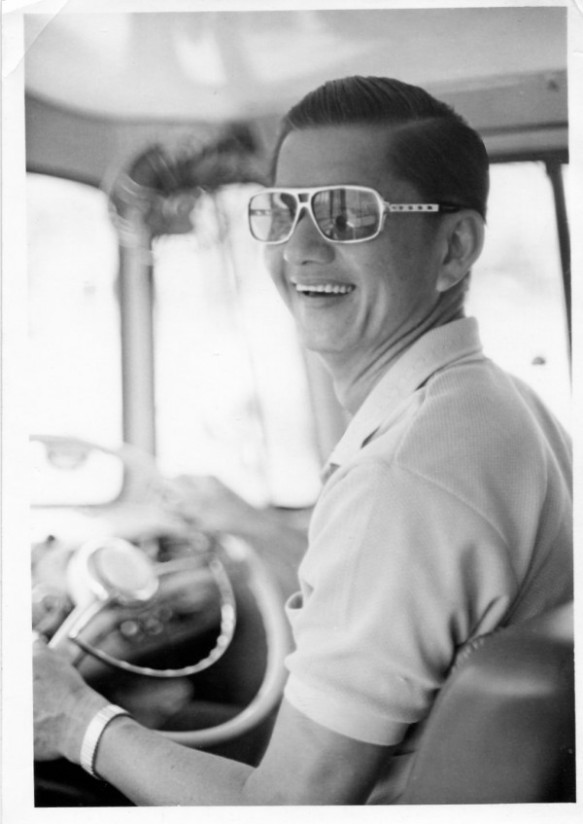

He borrowed money from friends to buy a bus and start a school bus run. He then started a factory bus run. He ran most of these ventures at the same time. On top of that, he somehow managed to find time to learn, and excel in, martial arts. And lead a martial arts school in Seremban, earning him the title of “Tang Sifu” (Master Tang) among his followers.

He even travelled to Port Dickson some twenty miles away once a week to teach additional night classes there. And he’d hire his bus to daytrippers on weekends driving them to the beachside resort of Port Dickson or to KL.

As a kid, I once found a very nice sketch of a girl back when we were living in Templer Flats. I tried to cut her out with a pair of scissors so I could play dress-ups with her, but with my poor scissor skills, I accidentally chopped her head off. Growing up in relative poverty does not preclude one from throwing a tantrum, and I did – I wanted whoever drew that picture to do another one.

Nobody owned up to it, so my stepmom helpfully tried to replicate the drawing to appease me. Her sketch was awful and I bawled my eyes out. It wasn’t until many years later that I found out the mystery artist was in fact my dad.

I’ll never fully learn the scope of my dad’s talents. I know that despite having very little education, he could speak every Chinese dialect, some of which are so obscure I’ve (still) never heard of them. He could communicate in Malay and seemed to have a better and quicker grasp of English on arrival in Australia than his much younger wife, despite never having learned either language formally.

Back in Malaysia he would watch English movies and TV shows without subtitles and understand the entire plot and get the gist of the dialogue without knowing the language. My dad never had the privilege of education, never had the luxury of indulging in his creativity and exploring his potential; he worked himself nearly to death, driving his buses till, on many occasions, he could no longer keep his eyes open.

And when it came to the dinner table, he always let his family eat first, claiming he was full until there were only scraps left for him. Only when my stepmom threatened to throw out the leftovers, would he reluctantly eat up. This pattern of behaviour continued his entire life, even when his kids were all grown up and we were no longer impoverished or in danger of ever going hungry again.

In “throwing away” all my higher education and promising career to pursue my passion for Malaysian food, my dad was the only person in my family who seemed to get it. My family doesn’t get it; my stepmom with her occasional nagging about my waste of a good education, and the deafening silence and lack of moral support from most other quarters are the kind of stuff I’ve resigned myself to.

And yet, the gleam in my dad’s eyes when he occasionally inquired about how things were going made it all worthwhile – he’d ask with a smile about adding this dish or that dish to my repertoire, or reminisce about his own experience in selling the same dishes back in his younger days.

The first time I was featured in a half-page spread in the Sydney Morning Herald’s Good Living section, he laminated a copy of it and kept it as a souvenir.

My dad is dying. He’s suffering from dementia and doesn’t have much time left. He sleeps most of the day and my stepmom looks after him. He shows signs of lucidity once in awhile, eg. when interacting with baby Noah, even if I doubt he really knows who he is.

Recently at family dinner, my brother-in-law who’s been in Australia probably about half a century, tried to crack a joke by speaking very broken Malay to my dad.

He gave up when he couldn’t remember the Malay word for “fishing”. My dad, seeming to be in his own little world up to that point, piped up – “pancing ikan!” Happy Father’s day, Dad. I love you.

Hi Jackie. My husband is Malaysian and I am always so interested in his stories. His world is so different from mine yet parallel. I find this post so poignant and I do relate. I guess the relationship between father and daughter in the east is very different. Before my Dad passed away last year, he too was suffering from dementia due to being ill for a long time. He was as he never was before; he was so funny, witty and for some reason only spoke in English. I treasure his last days as it was one of the happiest moments with him.

Thank you for the comments; yes, I, too, treasure these last days with him despite the circumstances. He comes up with some of the darnedest things when you least expect it 😀

Seremban girl…do we know each other? I recognize your dad’s picture. I used to take his school bus to convent seremban. I remember his smile like he had no worries in this world. Keep us posted how he’s doing. I had not been back in seremban for maybe thirty over years now. Take care.

Wow, small world indeed! I was at Convent Seremban until I left in Form Five in 1984 🙂

You have an amazing dad. Your dad & your family will be in my prayers Ms. J.

Thank you Raff 🙂

Beautifully written.

It takes age, maturity & possibly becoming a parent yourself to understand your own parents. My father was also tough on us & showed little affection growing up, but now that we’re older he has softened considerably… Or perhaps I have just come to understand how he expresses his love.

All the best for your father in his later years. I am sure he is immensely proud of you & all you have achieved.

Thank you Suz for the insight and kind comments 🙂

Poignant. A beautiful tribute.

Thank you Wendy 🙂

Just wanted to say, sounds like a great dad.

But, i’m sure you already know that,

Another friendly seremban boy.

You bet I do; thank you sir 🙂

This is so beautiful. The one thing about becoming an adult is that we begin to see our parents as the people they are, with less of a superhuman aura. So glad you have reached this place

Thank you Coqui Negra 🙂

Hi

I’m Chooi Peng/”Mimi”(as I call her) and Wilfred’s ‘s nephew. I spent some of my childhood in Seremban too (’80-’87). I don’t know if we have ever met though I doubt it as I don’t recall much contact with the Tang family – despite my being quite fond of Uncle Wilfred as a kid. He had a bike and a monkey!

I had only learned about your father’s Kung Fu mastery a few years ago when Wilfred, Mimi and Josh visited the UK and I was astonished to have never known this. I was greatly fascinated (I’m a Kung Fu geek).

I never knew your father’s name until I saw it mentioned on Facebook on Wilfred’s timeline. I Googled it and found your beautiful post.

Thank you for sharing these moments and I am sorry for your recent loss, but he seems a dad to be very proud of.

Thanks for the kind comments Kelvin, yes my dad was prince among men. I miss him greatly and hope to honour him through my work.

Amazing recount. These are memories worth cherishing. Most dads carry out their chores without a second thought about their own welfare.

We too, hope our kids may in time appreciate the things we go through and do.

Respect.

Thank you, John x

Beautiful recount. I think it is difficult for asian dads to show their emotions to their children, much as the way to. I can certainly relate.

Thank you, Liz, and yes, I very much agree x